Kyzyl-Kent. Паспорт объекта

Full description

Name: Kyzyl-Kenish, Kyzyl-Kent, Kyzyl-Kent Palace, Kyzyl-Kench Palace, Kyzyl-Ganch Palace, Kaz. Kyz-Aulie, oir. Xaslux. The Oirat name of the monastery is an assumption based on the analysis of the Oirat language biography of Zai-pandita Namkha-Jamtso. According to L. K. Chermak, there was a legend that the word “Kench” was from the kalmyk origin (Chermak: 211).

Object type: Ruins of a Buddhist temple, stupa, possibly a monastery (oir. Xeyid, süm-e) and a residence.

Founder: According to researchers, the founders of the monastery could be both Ochirtu Setsen-khan, the head of the khoshut community within the Oirat confederation, and Khundulen-ubashi, a khoshut aristocrat, uncle of Ochirtu Setsen-khan. See section Thematic maps. Khundulen-ubashi was the brother of Ochirt and Ablai Baybagas' father. To learn more about the lives of Ochirtu and Ablai, see the Article within the project.

Time and circumstances of foundation: Kyzyl-Kent was built in the 17th century during the domination of the Khoshuts in the central, southern and eastern parts of the Kazakh steppe. This period is also characterized by the spread and establishment of Tibetan Buddhism among the Oirats and Mongols. Tibetan Buddhism not only strengthened the ties of the Oirats with the Eastern Mongols, as well as with Tibet, but also contributed to their cultural development by introducing written culture, historiography, art, medicine and architecture. The Oirat nobility began to accept Tibetan Buddhism almost immediately after the Eastern Mongols did. Although the Tibetan lamas had been in contact with Oirat rulers long before that, from the beginning of the 17th century the Oirats adopted Buddhism traditions of the people with yellow-hats. The construction of stationary architectural structures in the Oirat nomads began even before the middle of the 17th century. The earliest monastery of the Oirats is Kabalgasun, which has been mentioned since 1616 as the town of the Durbet Dalai-Taishi. One of the earliest Buddhist monasteries was sume, founded by the Oirat lama Darkhan-Tsorji. The ruins of this monastery were still visible at the end of the 19th century near Semipalatinsk. Darkhan-Tsordzhiin-kit, apparently, was patronized by Khoshuts, possibly Ochirtu-Setsen, but there is no reliable information on this. Another point that possibly combined functions of a monastery, residence and fortress was the town built by Erdeni-Batur-khuntaiji in 1639 in the Kobuksar area. According to the archaeologist S.S.Chernikov, around the same years, the large and influential Khoshut aristocrat Ochirtu founded a small stationary monastery in the Kent mountains. Kyzyl-Kent laid on one of the main routes along which the Irtysh region was connected with the regions of the Ural and the Lower Volga, from the beginning of the 17th century occupied by the Oirat groups of Torguts and Durbets. Zh. O. Artykbaev calls it the “Kalmyk corridor” (Artykbaev 2001).

Archaeologist S. Chernikov cites a legend describing the history of the foundation of Kyzyl-Kent, referring to the data of the local historian V. Nikitin. According to this legend, the monastery, or rather the residence was founded by the Kalmyk warrior Aid-batyr, who stole the daughter of one of the Oirat khans (according to Nikitin, Kosan-Seren-khan) and, together with 40 young couples, took refuge in the Kent Mountains in the hope of sheltering from the endless wars between Kalmyks and Kazakhs. There, young people built a permanent residence Kyzyl-Kent for themselves. After some time, Aid-batyr is found by his brother Tleuke, who tries to persuade him to speak with him against the Kazakhs, but being refused, he kills Aid-batyr, but he himself soon dies in a battle with enemies (Chernikov 2018: 336; Nikitin). At the same time, Chernikov is does not trust the legend and puts forward his own version of the origin of the monastery. Based on the data of Gerhard Miller, Chernikov suggests that after Ochirtu received the title of Setsen Khan and ousted his brother and rival Ablai to Ural, he founds his monastery in five days' journey west from Ablai Kit. Since, according to Chernikov, no large Oirat buildings have been found to the west of Ablai-Kit, it can be assumed that in this case we can talk about Kyzyl-Kent. The disadvantage of this version is not only that the two monasteries are separated from each other by almost 500 km, which is difficult to cover in 5 days, but also that it does not find confirmation from other sources. Zh. O. Artykbaev and Zh. E. Smaylov rejected this version, reasonably pointing out that Ablai's nomadic migrations during this period were located in completely different places. This prompted them to develop other versions. According to Smailov's version, which was later picked up by I. V. Erofeev, the Kyzyl-Kent temple could have been built by the khoshut aristocrat Khundulen-ubashi. This is indicated by somewhat vague information from the biography of Zai-pandita Namkhai-Jamtso, where it was mentioned that in 1643 Khundulen-ubashi roamed in the Hasluk area, which Smailov identifies with the Kent mountains. Artykbayev, accepting this version, supplements it by giving priority to the Durbet Dalai-Taiji, which, in his opinion, even before the foundation of Kyzyl-Kent, built a stupa on the site around which the temple later arose.

Another story related to the Kyzyl-Kent palace was told by a local resident G. Sarsenbayev in 1986. Even earlier, the same legend was recorded by members of the expedition of F. Shcherbina at the end of the 19th century from the words of Sultan Akbay Zholda (Beisenov 2017: 469). Nikitin also mentions the name of this sultan (Akpai) and notes that the area was in his possession in 1895 for a hundred and fifty years (Proceedings of the Department of Russian and Slavic Archeology: 214). According to this legend, in 1697 in Kyzyl-Kent, Seterjap, the daughter of Ayuki, who was married to the Dzungarian ruler Tsewan-Rabdan, stayed in Kyzyl-Kent. It is said that at least one of the buildings in Kyzyl-Kent was built by an escort who accompanied the bride, and the famous Shono-Daba, the disgraced contender for the title of huntaiji and the hero of the epic tales of the Siberian peoples, was conceived in this place (Artykbaev 2001: 142). The legendary version about Seterjap, her connection with the nameless Kazakh batyr, the son of Seterjap, born of this connection and his ordeals, is also reported by L. K. Chermak (Chermak 1908: 211-218) from the words of the local old-timer Mukhametche. Nikitin also reports that this area in the past belonged to Bukuy Khan - the great-grandfather of Akbay Sultan, who found the palace already in decline.

Period of use: The version about the construction of Kyzyl-Kenish in the middle of the 17th century received support from a number of authoritative researchers, such as I. V. Erofeeva or Zh. O. Artykbaev, but it is still not proven. The story of Seterjap can speak in favor of the later dating of the monument - the end of the 17th century. One way or another, however, archaeological research data indicate that the monument was used for a short time. According to the reports of Akbay Sultan recorded by Nikitin, his grandfather Dzhildy Khan and father Siil Khan drove their rams into the premises of the palace in a bad weather.

Main functions: What were the objectives of the construction of Kyzyl-Kent is a debatable issue. The generally accepted point of view is that Kyzyl-Kent was a Buddhist monastery built by one of the Khoshut aristocrats. Really the mandala structure of the main building resembles a Tibetan Tantric temple. The premises surrounding the temple were apparently residential or auxiliary. According to one version, one of the buildings could have been a stupa (suburgan) (see Usmanova, Bedelbaeva 2017: 333). Another room housed an oven and a grain grinder.

Religious affiliation: Buddhism of the Tibetan Gelukpa tradition (Tib. Dge lugs pa), or the yellow-hats’ tradition (Tib. Zhwa ser), founded by the prominent Buddhist thinker Je Tsongkhapoi Lobsan-Dakpa (1357-1419). Gelukpa is the most widespread Tibetan tradition that has spread in the Mongol and Oirat community since the end of the 16th century. See section Thematic maps.

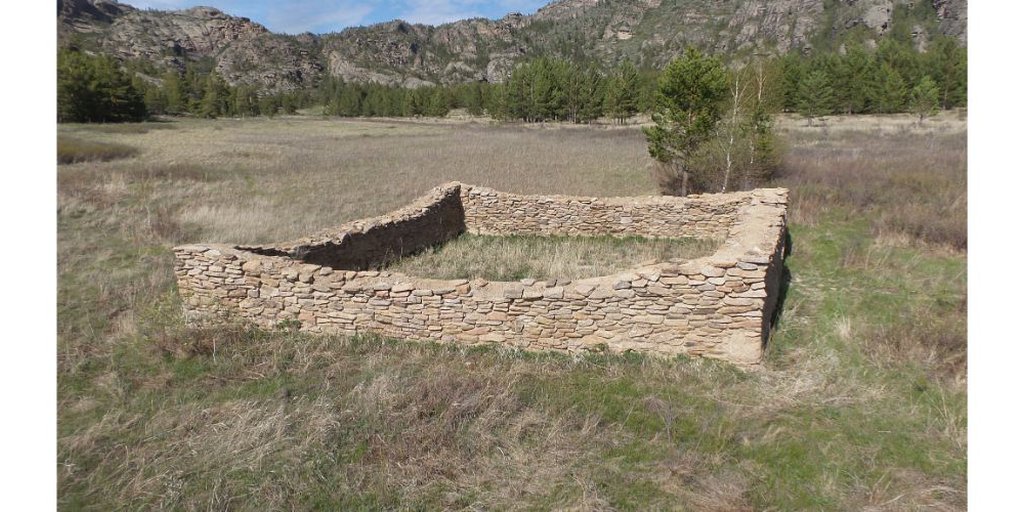

Plan: The monument consists of four destroyed and partially restored buildings, the main of which has a cruciform manadlov-like shape. The walls of the buildings were originally constructed of raw limestone, bonded with clay mortar. During excavations, archaeologists found the remains of wooden structures. The main temple consisted of a main room, each side of which was 12 meters, and small rooms adjacent to it on three sides. Inside the main room there were granite bases for the columns that supported the vault. From the south, there is a portico, which consisted of several pillars, adjoined the main room. The earliest descriptions of the site that have come down to us date back to the 20s of XX century when the monument was examined first by General S. V. Bronevsky, and then by Professor of the University of Dorpat K. A. Meyer. According to Meyer, the walls of the main building were made of roughly hewn granite stones bound with clay. Meyer noted that he clearly saw that the building in all parts had ceilings for the second floor. Already in his time, neither the second floor nor the roof survived. A door led into the temple, and small rooms adjoining the main room were also separated by doors. There were small windows in the northwestern and southeastern rooms. He notes that he did not notice any decorations or other signs by which one could determine the character of this building in a functional sense. However, according to his information, local Kazakhs considered the place as holy and sacrificed horse hair, sheep's wool and old rags, which were attached to a pole and left in the portico (Ledebour et al. 1993: 331).

Nikitin reports that the entrance to the premises was arranged under a canopy that "looks like a balcony and is supported by six wooden posts." The height of the pillars was up to 4 arshins (about 3 meters). Probably, there was a second floor above the main room, which is also confirmed by Nikitin's descriptions. There is a photo of the dilapidated main building, on which the structure of the portico is clearly visible. According to Nikitin, who examined the monument in 1895, the height of the preserved walls of the main building at that time did not exceed one fathom (about 2 meters). Three other buildings were located close to the main temple. One of them, most likely, was not a room, but a stupa, or a funeral cult structure. It was plundered. Another building was residential or utility. The evidence for that is that there are remains of a furnace inside it. The last room most likely was a residence. In our opinion, assumptions that it was cult and there were sacrifices carried out in it (Usmanova, Bedelbaeva 2017: 333)contradict the nature of Tibeto-Mongolian Buddhist temples. In front of the main building, there is still a recess, which in the past could have been a well or an artificial water reservoir. Nikitin reports that at the end of the 19th century there was an overgrown pond, but with reeds. See the photo gallery.

Features of the landscape: The monastery was built in a gorge at the southern foot of the Domolaktas mountain in the Kent mountains, 260 kilometers southeast from Karaganda city and 37 km southeast from Karkaralinsk. The Kent Mountains served as a natural protection for the Kyzyl-Kenishu from the north. See photo gallery.

Current state: The excavations of Kyzyl-kenish were started in 1985 by employees of the “Kazproektrestavratsiya” Institute of the Ministry of Culture of the Kazakh ASSR under the leadership of Zh. E. Smailov and A. Z. Beisenov (Usmanova, Bedelbaeva 2017: 331; Artykbaev 2001: 136). In 2008-2009. the research has continued by the participants of the Kazakh Research Institute by the problems of the cultural heritage of nomads (the project leader is the director of the institute, Ph.D. I. V. Erofeeva). During the restoration work in the 1980s, on the remains of the foundation the walls of all buildings were erected to a height higher than a human height.

Threats: The "restoration" of the monument structures is rather a dubious way to preserve it. The best way to preserve it is to preserve the monument in the form in which it was discovered by archaeologists. The monument is now included in the register of objects of national importance and is protected by the government. The rest zone next to it is fenced and ennobled. Nevertheless, the monument is potentially under the threat of vandalism or destruction due to the negative image of the Oirats, or Dzungars, which is widespread in the mass consciousness.

The nearest settlement: The object is located 37 kilometers southeast from the town of Karkaralinsk. See photo gallery. There are no buildings on the site itself. There is only a gazebo and information stands.

Other sites: There is another important archaeological site, the Kent settlement of the Late Bronze Age, 3 kilometers away on the SVV. See photo gallery.

Aul Kent: Small settlement (about 30 yards).

Road: From Karkarlinsk to the village Karagaily you can reach by the asphalt highway A345 and R-200. From Karagaila to the village of Kent and further to Kyzyl-Kent there is a dirt road, which can be flooded with water during the period of rains and floods. Thus, access to the monument can be difficult in spring and summer.

Artifacts and manuscripts: Elements of staples, bronze plates, samples of an architectural decor, a fragment of a bronze mirror, combs, earrings, beads, Chinese coins, a gun bullet, etc. were found at the site. See the photo gallery.

Assessment of the current state. The Kyzyl-Kent Palace today is included in the list of sacred sites of Kazakhstan of regional significance in the Karaganda region. The monument is under state protection. After conducting archaeological excavations in 1986-1987, the site has undergone a partial restoration by the “Kazproektrestavratsiya” Institute of the Ministry of Culture of the Kazakh SSR and is currently mothballed.

Investment Recommendations: Kyzyl-Kent is an attractive tourist destination. It is one of the few survived examples of the earliest Oirat Buddhist architecture in the territory of Kazakhstan. The site is located in Kent Mountains at the foot of Mount Domolactas. In this area, there are also important archeological sites of the Middle Ages and the Bronze Age, as well as old Kazakh mazars, including the settlement of Bolshoi Kent, on the territory where the remains of 130 buildings have survived. All of this makes the Kyzyl-Kenish complex of monuments an attractive place for tourists who get a unique opportunity to see the picturesque landscapes of the Kent mountains, Mount Domolaktas, wander among the ruins of the Oirat monastery, and also learn more about the ancient history of Kazakhstan. At the same time, the ruins of the Kyzyl-Kenish monastery can become part of the route dedicated to the Oirat world and the Buddhist geography of Kazakhstan, if you combine such sites as Ablay-kit, Semipalatinsk, Konyr-Aulie and Kyzyl-Kenish into a single route. It would be also possible to build a model of a monastery next to the ruins of the monasteries.

Recommended sources:

Артыкбаев Ж. О. Кызыл-Кенчский дворец - малоизвестный памятник калмыцкой архитектуры в Центральном Казахстане // Монголика 2001.

Бейсенов А. З. Кызылкеныш. Комплекс памятников / Cакральная география Казахстана: Реестр объектов природы, археологии, этнографии и культовой архитектуры / Под общей редакцией академика НАН РК Байтанаева Б.А. – Алматы: Институт археологии им. А.Х. Маргулана, 2017. – Вып. 1. C.464-473.

Ерофеева И. В. Ламаистский монастырь Кызылкент // Атлас репрезентативных памятников природы, истории и культуры Казахстана. Алматы, 2010.

Ерофеева И. В. Памятники Тибетского буддизма середины XVII – первой половины XVIII века в Казахстане: новые исследования и находки // Научные чтения памяти Н.Э. Масанова. Сб. материалов научно- практической конференции. Алматы, 2009.

Кукеев Д. Г. Об оседлых поселениях на территории Евразии // Mongolica-XII. Сборник научных статей по монголоведению. Посвящается 130-летию со дня рождения Б.Я.Владимирцова (1884—1931). – СПб.: Петербургское востоковедение, 2014. – С. 26-35.

Ледебур К. Ф., Бунге А. А., Мейере К. А. Путешествие по Алтайским горам и джунгарской Киргизской степи. Отв. ред. О. Н. Вилков и А. П. Окладников. Новосибирск: «Наука», 1993.

Никитин В. П. Семипалатинская область / Записки Императорского русского географического общества. Том VIII, вып. 1 и 2.Новая серия. Труды отделения русской и славянской археологии. Книга первая. 1895. С-Петербург: Типография И. Н. Скороходова, 1896. С. 212-215.

Смаилов Ж. Е., Бейсенов А. З. Кызылкентский дворец (КызАулие) // Восточная Сарыарка. Каркаралинский регион в прошлом и настоящем. Алматы, 2004.

Усманова Э. Р., Бедельбаева М. В. Ойратский монастырь Кызылкент в Центральном Казахстане: новые находки / Ойрад монголчуудын биет бус соёлын өв. Олон улсын эрдэм шинжилгээний V хурлын илтгэлийн эмхэтгэл. Улаанбаатар, 2017.

Чеканинский И. А. Развалины Кзыл-Кенш в Каркаралинском округе Казахской АССР // Записки Семипалатинского Отдела общества изучения Казахстана. Т. 1. Семипалатинск, 1929.

Чермак Л. К. Кзыл-кенчь (Киргизская легенда) / Сборник в честь семидесятилетия Г. Н. Потанина. С-Петербург: Типография В. Ф. Киршбаума (отделение), 1909. С. 211-218.

Черников С. С. Памятники архитектуры ойрат-калмыков // Записки Калмыцкого НИИЯЛИ. Вып. 1. Элиста, 1960.

Photo gallery

Map

Materials

All materials are available at the following link